MacMahon Master theorem

The MacMahon Master theorem (MMT) is a result in enumerative combinatorics and linear algebra, both branches of mathematics. It was discovered by Percy MacMahon and proved in his monograph Combinatory analysis (1916). It is often used to derive binomial identities, most notably Dixon's identity.

Contents |

Background

In the monograph, MacMahon found so many applications of his result, he called it "a master theorem in the Theory of Permutations." The result was re-derived (with attribution) a number of times, most notably by I. J. Good who derived it from his mulilinear generalization of the Lagrange inversion theorem. MMT was also popularized by Carlitz who found an exponential power series version. In 1962, Good found a short proof of Dixon's identity from MMT. In 1969, Cartier and Foata found a new proof of MMT by combining algebraic and bijective ideas (built on Foata's thesis), and further applications to combinatorics on words. Since then, MMT became a standard tool in enumerative combinatorics.

Although various q-Dixon identities have been known for decades, except for a Krattenthaler–Schlosser extension (1999), the proper q-analog of MMT remained elusive. After Garoufalidis–Lê–Zeilberger's quantum extension (2006), a number of noncommutative extensions were developed by Foata–Han, Konvalinka–Pak, and Etingof–Pak. Further connections to Koszul algebra and quasideterminants were also found by Hai–Lorentz, Hai–Kriegk–Lorenz, Konvalinka–Pak, and others.

Finally, according to J. D. Louck, theoretical physicist Julian Schwinger re-discovered the MMT in the context of his generating function approach to the angular momentum theory of many-particle systems. Louck writes:

- It is the MacMahon Master Theorem that unifies the angular momentum properties of composite systems in the binary build-up of such systems from more elementary constituents.

Precise statement

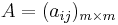

Let  be a complex matrix, and let

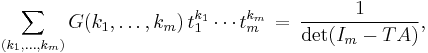

be a complex matrix, and let  be formal variables. Consider a coefficient

be formal variables. Consider a coefficient

Let  be another set of formal variables, and let

be another set of formal variables, and let  be a diagonal matrix. Then

be a diagonal matrix. Then

where the sum runs over all nonnegative integer vectors  , and

, and  denotes the identity matrix of size

denotes the identity matrix of size  .

.

Derivation of Dixon's identity

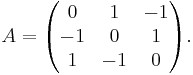

Consider a matrix

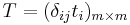

Compute the coefficients G(2n, 2n, 2n) directly from the definition:

where the last equality follows from the fact that on the r.h.s. we have the product of the following coefficients:

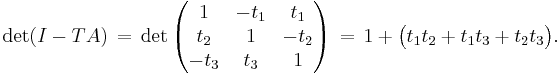

which are computed from the binomial theorem. On the other hand, we can compute the determinant explicitly:

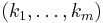

Therefore, by the MMT, we have new formula for the same coefficients:

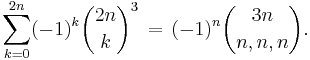

where the last equality follows from the fact that we need use an equal number of times the all three terms in the power. Now equating two formulas for coefficients G(2n, 2n, 2n) we obtain an equivalent version of Dixon's identity:

References

- P.A. MacMahon, Combinatory analysis, vols 1 and 2, Cambridge University Press, 1915–16.

- I.J. Good, A short proof of MacMahon's ‘Master Theorem’, Proc. Cambridge Philos. Soc. 58 (1962), 160.

- I.J. Good, Proofs of some `binomial' identities by means of MacMahon's ‘Master Theorem’. Proc. Cambridge Philos. Soc. 58 (1962), 161–162.

- P. Cartier and D. Foata, Problèmes combinatoires de commutation et réarrangements, Lecture Notes in Mathematics, no. 85, Springer, Berlin, 1969.

- L. Carlitz, An Application of MacMahon's Master Theorem, SIAM Journal on Applied Mathematics 26 (1974), 431–436.

- I.P. Goulden and D. M. Jackson, Combinatorial Enumeration, John Wiley, New York, 1983.

- C. Krattenthaler and M. Schlosser, A new multidimensional matrix inverse with applications to multiple q-series, Disc. Math. 204 (1999), 249–279.

- S. Garoufalidis, T. T. Q. Lê and D. Zeilberger, The Quantum MacMahon Master Theorem, Proc. Natl. Acad. of Sci. 103 (2006), no. 38, 13928–13931 (eprint).

- M. Konvalinka and I. Pak, Non-commutative extensions of the MacMahon Master Theorem, Adv. Math. 216 (2007), no. 1. (eprint).

- D. Foata and G.-N. Han, A new proof of the Garoufalidis-Lê-Zeilberger Quantum MacMahon Master Theorem, J. Algebra 307 (2007), no. 1, 424–431 (eprint).

- D. Foata and G.-N. Han, Specializations and extensions of the quantum MacMahon Master Theorem, Linear Algebra Appl 423 (2007), no. 2–3, 445–455 (eprint).

- P.H. Hai and M. Lorenz, Koszul algebras and the quantum MacMahon master theorem, Bull. Lond. Math. Soc. 39 (2007), no. 4, 667–676. (eprint).

- P. Etingof and I. Pak, An algebraic extension of the MacMahon master theorem, Proc. Amer. Math. Soc. 136 (2008), no. 7, 2279–2288 (eprint).

- P.H. Hai, B. Kriegk and M. Lorenz, N-homogeneous superalgebras, J. Noncommut. Geom. 2 (2008) 1–51 (eprint).

- J.D. Louck, Unitary symmetry and combinatorics, World Sci., Hackensack, NJ, 2008.

![G(k_1,\dots,k_m) \, = \, \bigl[x_1^{k_1}\cdots x_m^{k_m}\bigr] \,

\prod_{i=1}^m \bigl(a_{i1}x_1 %2B \dots %2B a_{im}x_m \bigl)^{k_i}.](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/e040fe5a1a487b267bb72e941f2f5d48.png)

![G(2n,2n,2n) = \bigl[x_1^{2n}x_2^{2n}x_3^{2n}\bigl] (x_2 - x_3)^{2n} (x_3 - x_1)^{2n} (x_1 - x_2)^{2n} \, = \, \sum_{k=0}^{2n} (-1)^k \binom{2n}{k}^3,](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/68d0873f3efad5c59be64d135dde55d7.png)

^{2n}, \ \ [x_3^k x_1^{2n-k}](x_2 - x_3)^{2n}, \ \ [x_1^k x_2^{2n-k}](x_1 - x_2)^{2n},](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/b5087bbc81449dda1bebd62820eae348.png)

![G(2n,2n,2n) \, = \, \bigl[t_1^{2n}t_2^{2n}t_3^{2n}\bigl] (-1)^{3n} \bigl(t_1 t_2 %2B t_1 t_3 %2Bt_2t_3\bigr)^{3n} \, = \, (-1)^{n} \binom{3n}{n,n,n},](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/cb3e502e70aa6973e664125396773c5f.png)